A Social History of Felt in Canada: Part 5

A Story of Immigration:

To the Prairies where felt is good for the sole…

LEFT: Valenki, early 1900s, made in Russia

CENTRE: Men’s boots with felt soles and uppers, 1930s, made in Canada

RIGHT: Women’s boots with felt soles and uppers, 1930s, made in Canada

All on loan for exhibition from the Ukrainian Museum of Canada, Saskatoon

Through the late-ninteenth century Canada earnestly promoted immigration, marketing itself as a land of opportunity, in efforts to guarantee sovereignty of colonial land claims and provide a catalyst to economic growth. Policies favoured British and Northern Europeans but others were wooed in order to increase the population.

Ukrainians, the name that Canada applied to all Slavic people from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian regions of eastern and southern Europe, made up a large part of this wave of migration. The promise of farmland drew 170,000 rural poor to Canada’s prairies between 1891 and 1914. They settled across Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, most as homesteaders, some as domestic workers and wage workers in resource industries. But, the optimism crashed with the outbreak of World War 1 when Ukrainians were classified as enemy aliens, and many were interned in camps even as 10,000 enlisted in the Canadian armed forces.

The Ukrainian migration from oppression under Russian rule to continued hardship in Canada is reflected in a collection of well-worn boots from the Ukrainian Museum in Saskatoon. In the early days Russian Valenki, common in Ukraine, proved to hold up well in the cold dry winters of the prairies while a subsequent wave of migration between the wars saw these settlers adapting to their new home, finding similar warmth and protection in felt boots made in Canada.

Canada built an impressive felt boot industry through the twentieth century, producing and distributing styles for comfort and warmth against the winter cold. Felt was used as boot uppers, and also for the soles. With increasing urbanization felt soles became less practical. Now felt is most common as liners and insoles though most of these, originally made of wool, have been replaced by cheaper synthetic felts. KW

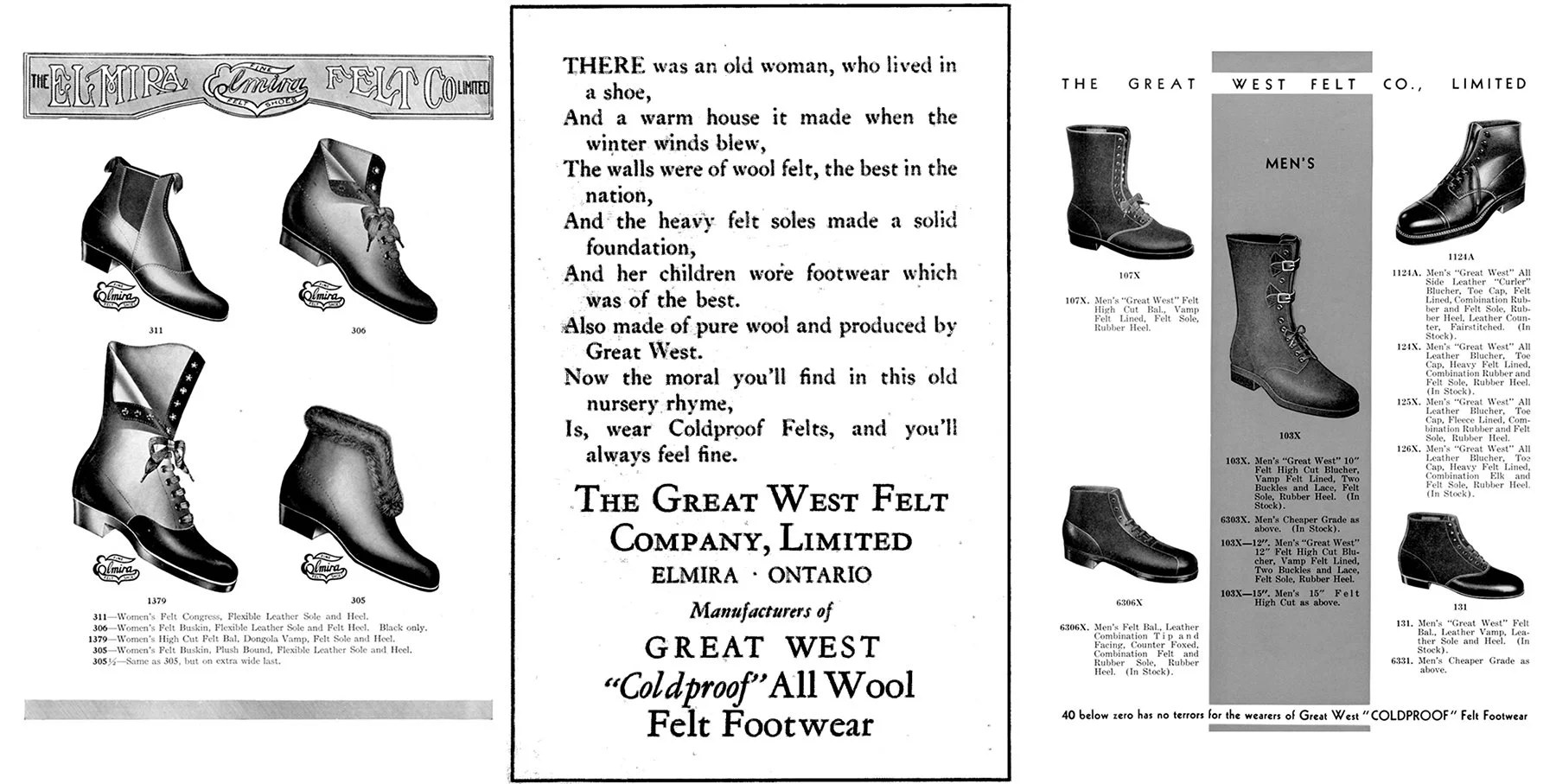

Advertisements for the Great West Felt Co. Ltd, Elmira ON, 1930s